On the surface, we seem to be living in a golden age of craftsmanship. Luxury brands are enjoying years of steady growth, hiring and training new artisans and building new factories across the world from Texas to France. Content creators, luxury brands, journalists and influencers sing the praises of craftsmanship or at least mention it as a normal part of their coverage of fashion, style and luxury. Customers with disposable income from Dallas to Dubai seem keen to buy craft. What’s not to like?

If you truly care about craft, the reality is less rosy. Manual labor, artisanal work and traditional crafts are perhaps more endangered, marginalized and misunderstood than ever before. The absolute numbers of artisans have fallen precipitously in the last 50 years. I see this everywhere I travel. Mid-sized Italian towns that used to have hundreds of tailors just a few decades ago now are served by just one lone tailor.

The reasons for this decline are both material and ideological. We live in an age of globalized cost arbitrage, automation, data, and artificial intelligence. The economics of our age render nonsensical any rational use of handwork. Today’s profits are made by using low cost labor to make things or deploying machines (servers in the cloud) to crunch personal data generated by us.

In turn, these technological and material conditions shape how we view craft. Today’s consumer brands are less concerned about craft and manufacture than they are about removing friction in the customer experience. Convenience over craftsmanship – some call it the “tyranny of convenience”.

Even worse, craft is hardly on the radar for policymakers, legislators, investors, and others in a position to make a difference. This gap is even bigger among content creators and influencers in fashion. When was the last time you saw a politician, an influencer or wealthy investor materially improve the underlying sustainability of craft and the livelihood of artisans? I’m hard pressed to think of any. Virtually no one is pressing the cultural, economic and practical case for craft.

So what does craftsmanship mean in an age of global supply chains, intelligent machines, convenience and indifferent elites? Perhaps more to the point, what should craft look like in the 21st century and what can we do about it? Let me offer three perspectives – historical, customer and cross-cultural – and then blend them into an argument about what it should mean for anyone interested in craft today.

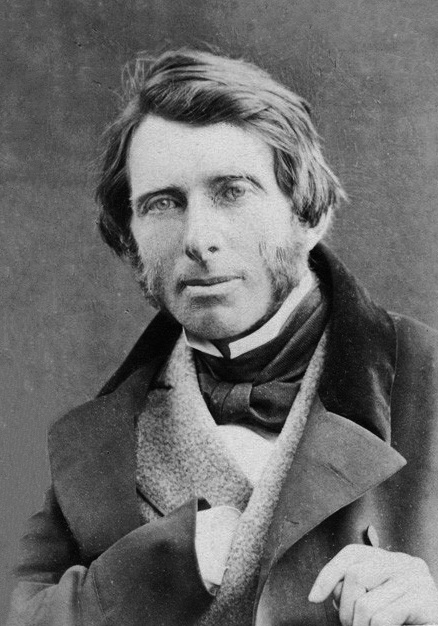

Let’s start with the historical perspective and pay homage to the source and wellhead of craft. This year is the 200th anniversary of the birth of the English art and social critic John Ruskin (1819-1900). He was also an accomplished artist in his own right. Although the bicentennial has led to some thoughtful reflection of his relevance today, further recognition is in order.

Ruskin was the philosophical inspiration and undercurrent to my post on the artisan’s dilemma. I’ve concluded that he and his fellow Victorians – despite their fusty and problematic worldview – were right after all on the importance of craft. They were horrified at the human cost of industrialization and the punishing conditions imposed on the laborers of the day. They were concerned about the impersonal logic of machines and capital and how that might erode the meaning and dignity of labor.

Propelled by these concerns, Ruskin’s writing established the philosophical foundations of modern craft. Although Ruskin is the writer and thinker most responsible for today’s concept and meaning of craftsmanship, very few know him. We need to reacquaint ourselves with his answer to the question “what is craftsmanship?” His farsighted, holistic response is sorely needed in our age of convenience and corporate luxury brands.

For Ruskin, craftsmanship means the ability and willingness of the artisan to move fluidly from design to execution. This is the ethical-aesthetic imperative of craft. Design (“thinking”) should not be alienated from execution (“doing”) or vice versa. Craftsmen and women should be free and motivated to shape the design and creation of the entire product. They should be present at the creation and orchestrate its development directly or relationally at each stage.

Ruskin argues we ought to respect the artisan’s wide-ranging ability and desire to integrate the entirety of her creation, not merely work on bits and pieces of it. This is the hallmark of genuine, meaningful and sustainable craftsmanship. Put another way, Ruskin refashioned and revivified the Enlightenment humanist tradition for the industrial context of the late 19th century.

Ruskin’s argument is more valid today than ever before. We’re not genuine artisans unless we’re able to transform an idea in our head and heart, and realize it with our own imagination, planning, know-how, relationships and tools. His vision of craft relies on creative autonomy, relational creation with peers and end-to-end fluidity. All of this has significant implications for a sustainable artisanal economics.

As a point of contrast, let’s look at a recent GQ advertorial entitled “The Fine Craft of Fashion“. The photo essay featured a Dior Men’s shirt designed by Kim Jones with a suggested retail price of $650,000. Thinking this was perhaps a misprint, I went to the GQ website and corroborated the six figure price. The article makes a point of describing the Maison Lemarie workshop that realized the shirt – how the shirt needed 15 people and a total of 900 hours to embroider 2,000 feathers.

This may be so but who is the architect and who reaps the rewards of all this labor? The craftspeople? Think again. I estimate that the monthly salary of an entry-level luxury craftsperson to be around EUR 3,000 – 4,000. This implies a total labor cost of EUR 20-30,000 to produce the Dior shirt, which is priced at $650,000. Knowing the selling price and labor cost allows us to estimate the gross margin of the shirt. This margin vastly exceeds earned wages even after accounting for material costs. But this is what happens when artisans are organized within a corporate luxury brand. By default, artisans are never among the most well-compensated ranks in a corporatized luxury brand.

Luxury brand managers and executives will certainly praise artisanal work and craftsmanship as essential to their business. But they are also incentivized to contain, anonymize and subordinate artisans within an organizational hierarchy. Artisans will always be secondary to financial priorities, management goals, the brand’s DNA, the designer’s point of view, the creative brief or the founder’s vision.

If you doubt this, simply look at Bernard Arnault, founder of LVMH, the world’s largest and most successful luxury conglomerate. His success rests on a simple logic – “he has always placed the brand above the individual…” Arnault intuited decades ago that certain brands possess the power to uniquely activate consumer desires, attention and aspirations around the world. In this particular vision of luxury, artisans are necessary but not sufficient to deliver such a brand.

In a recent Vogue piece on Valentino, the magazine described a couture fitting in Rome: “…there are seven craftspeople, each wearing the traditional white laboratory coat, painstakingly hand-rolling 1,700 meters of tiny ruffles of oyster organza and finishing them with minuscule stitches for a single dress that will ultimately require more than 1,000 hours of work.” Note the anonymity of the seven craftspeople, rendered even more homogenous by the wrong-headed notion that white laboratory coats are signs of craftsmanship and that craft is reducible to hours of work.

Craft is not simply hours of work or even skill burnished by time and experience. It is certainly not reducible to anonymous workers in lab coats. Craft expresses something far more fundamentally human, namely, the idea and practice of “care”. Artisanal craft is attention and care shaped by hard-earned knowledge and training.

Care is the word that Guido Davi, a Sicilian tailor, shared with me one day in his workshop. It took me some time to fully understand the deeper meaning of this word and its relationship to craft. At a basic level, it means being present and responsible for the artisanal process. At a practical level, care is exercised by specific persons with specific names, histories and habits.

Care further requires directness and closeness to the artisanal locus of activity. As Ruskin put it, “local is logical”. This means the artisan (or a team connected to the artisan) orchestrates and performs the work. There is also clear custodianship of care, traceable forward and backward at each stage of the process.

Genuine craftsmanship integrates all of this – attention, care and knowledge expressed by persons with genuine agency and responsibility to exercise their judgment throughout the process. Craft is not diluted or segregated in factories far away from management teams and executive committees. If you care about something, you must be close to its locus of creation.

Unfortunately, you’ll never get the fullest expression of this integrated artisanality – its organic, traceable custody of care – from a corporatized luxury brand. Go to any store of a well-known luxury brand. Who are you buying from? The artisan or a salesperson? It’s always the salesperson. Your salesperson may have visited one of a dozen factories that make your bag, shoe or suit but she is far removed from the artisan.

In corporatized luxury, the reality of retail sales targets always competes against the fullest expression of artisanal intent and integrity. This conflict is a necessary organizational consequence of modern luxury brands. The sales floor is measured by sales per square foot. The artisan’s world and ethos is measured by care and proximity.

Let’s turn now to the customer’s idea of craft. Often craft is thought of simply as skilled manual labor or handwork. This is a gross simplification. But perhaps the greatest customer misconception is that craft results in “perfection”. Customers often believe a well-made product is about perfection measured against an objective standard of quality. It’s repeated so often that even artisans themselves have come to believe in it.

The achievement of perfection does occur in certain endeavors, most notably in sports, mathematics or other scored and measurable activities. One thinks of baseball’s “perfect game”, perfect win-loss records or scoring a perfect 10 in judged competitive sports like gymnastics. But in many other human activities the idea of perfection is irrelevant, misconceived and possibly even dangerous.

Take the fine arts or performing arts. Is it sensible or even relevant to think of a musical composition, painting or work of literature as truly perfect in all respects? What does that even mean?

For me, there is something off about demanding perfection in certain endeavors like craft. If anything, the more appropriate way to properly view perfection in this context is serendipity. Something close to perfection might be possible but it is not the artisan’s goal. Instead, craft is better thought of as the pursuit of a certain kind of integrity.

This integrity is illustrated by the following quote from the venerable English shoemaker Crockett & Jones:

Source: Crockett & Jones

True perfection requires superhuman consistency which cancels out the humanness of craft. Craftsmen and women might repeatedly strive for perfection. But they cannot consistently produce it. Call it the artisan’s paradox.

In the end, we need a different lens and vocabulary to understand and sustain craft, especially as customers. In the near future, I will publish a separate article on how we can become better artisanal customers since we have such an outsized impact on the viability of artisanal businesses.

For now, let me end on the Japanese practice of kintsugi, which means “golden joinery or repair” of broken pottery. Kintsugi is the intentional practice of incorporating natural faults, breaks and cracks into pottery. It means we ought to preserve and repair pottery, respecting the original care and intention behind it, rather than discard or reject it.

This has deeper implications for what craftspeople do and how customers should treat them. At its core, this is a philosophy of anti-perfectionism closely related to the Japanese concept of wabi-sabi. To fully appreciate what artisans do, I believe we should spend less time demanding “perfection” in bespoke “products” and more time understanding and respecting craft and artisan.

As customers, we certainly have a say in bespoke creations. But we should also think more about the care and intention that led to what you are wearing and to the artisan(s) who crafted something out of nothing. Equally important is the artisans’s relationship to her creation and your relationship with the artisan. All three elements should be in harmony.

When that happens, I believe your sense of accountability and perspective will shift. You are not simply a consumer of artisanal products but a curator (from the Latin cura or care) of the artisan and her craft. In other words, not merely a consumer but a caretaker. This implies a certain kind of responsibility.

In the end, craft is a very human process joining people, places, ideas and things. It is not simply a transaction or a product meant to serve the consumer. If we find a way to recognize and respect this, we will be much better positioned to ensure a place for craft in our increasingly convenience-driven and automated future.

This very thoughtful article provides insight into the public’s perception of what is considered craft in the context of fashion.

One point which may be raised is that although the share of the atelier workers’ gain against the retail price of the garment is small, the corporation is providing income security which an independent craftsman does not have. To many people, being an employee is more preferable than becoming a sole proprietor. This is perhaps even more so in continental Europe, where employees enjoy certain protections, and being a business owner is less celebrated than in the Anglophone world.

Furthermore, the shirt itself is simply a standard men’s shirt with embellishment. The fact that GQ considers it the “apex” of craftsmanship is telling vis-a-vis the general public’s perception of the trajectory of men’s dress. It is indicative of the feminization of menswear.

Standardized luxury menswear serves its purpose. Some may consider it perfect in the sense that it is produced with luxury fabrics, and is guaranteed against irregularities in size and quality. For most people this is perfection.

A bespoke garment cannot be perfect in this context as it is cut to fit an individual: there is no standard for it to deviate from. Therefore, perfection when compared to a ready-to-wear garment is incongruent.

Clearly what Kim Jones and Dior are engaged in is artifice and spectacle.

I feel that it is sisyphean for independent artisans to contend with LVMH and SR. I feel that the problem which must be addressed is consumer education, and the need to raise awareness of the existence of independent bespoke tailoring.

These are all excellent points, especially the point about distinguishing two types of artisans – independent v. employed artisans. They are quite different and there is certainly room for both types. I’d agree that for many being an employee is the preferred route and no different than most careers and professions. I suppose my only concern is that we seem to be switching almost completely from a world of primarily small and independent artisans to a world of corporate artisans. I wish more artisans were independent which is closer to the origins of craftsmanship.

I also enjoyed your point about bespoke not being perfect because “there is no standard to deviate from”. Exactly! Very helpful perspective for those who are buying bespoke or thinking about it. It’s a different animal than RTW.

On the other hand, I just heard that Corneliani, the classic Italian menswear brand, is laying off 130 workers in its factory in Mantua. The lack of job security can be remarkably indiscriminate.

Pingback: Sicilian tailoring in Ragusa - a sartorial gem worth keeping | Sleevehead

Pingback: 7 rules on becoming a better bespoke customer | Sleevehead